What is a good length for bowlers looking for seam movement?

Subscribe on Substack, via RSS/Atom, or follow me on Twitter for updates

Watching the World Test Championship and the England-India series recently, I noticed the preponderance of wickets taken by seaming deliveries, which made me ask, what is a good length for bowlers looking to get movement off the pitch? We typically see it shown as between 6 to 8 metres on television broadcasts and in writing. But, why is that a good length? In an interesting article for ESPNCricinfo’s Cricket Monthly in 2018, Nathan Leamon argues, using a combination of an average fast bowler’s ball coming off the pitch at 32 metres per second, a range for batter reaction times between 120ms and 200ms, and extra 1-2 metres of perception distance, that a ball pitched pitch between 6-8 metres is one that “gives the ball the most room to deviate and beat the bat, without giving the batsman time to adjust to that deviation.”1 Leamon then shows how data on batting averages for various lengths confirm this, with the 6-8 metre length having the lowest average. Leamon also goes on to discuss more broadly the “best length” to bowl and the strategy of bowling fuller and the effect of swing and seam. If you are interested in a detailed data driven approach to cricket Leamon’s article is worth reading in full.

However, Leamon’s article did raise some questions for me that were not answered. The first is, what is a safe assumption on the average batter’s reaction time? Unfortunately, Leamon does not cite any of the research on batter reaction times, so it is hard to see where the figures come from, especially given a moving bat requires more time than simply reacting to visual stimulus. Another question was how much do bowling speeds, which vary from bowler to bowler, and angles of deviation, which vary from pitch to pitch, affect a good length? Leamon relies on averages of bowling speeds and angles of deviation for his analysis. This makes it hard to see how much those variables have an effect on estimating a good length. Bowling speeds vary quite a lot especially if we consider both men’s and women’s cricket, and pitches also vary a lot in how much deviation they offer. Given all that, in this post I want to tease out in more detail how a good length (or more accurately the maximum and minimum good length) can be estimated by looking at the research on batter reaction times and pitch behaviour.

As far as I could find, the experimental research on cricket batter reaction times began in the late 1980s. Peter McLeod in 1987 measured the reaction times of first-class batters by using a bowling machine to bounce balls at various lengths on a surface that induced lateral movement.2 He found that no batter could adjust to the lateral movement after a ball bounces in less than 190-200 milliseconds (53). When he measured “overpitched” balls, that is balls bounced 100ms or less away from the batter there was no adjustment. When balls were bounced at a “good length” about 160ms away from the batter, no adjustment was observed until 190ms after the ball had bounced. When he measured “short pitched” balls, that is balls bounced 400ms away from the batter, McLeod observed adjustment to the lateral movement of the ball around 210ms after the ball had bounced but nothing before.

What explains these reaction times? Michael F. Land and Peter McLeod in 2000 measured the eye movements of batters of different skill levels to determine what visual information they actually used to hit the ball.3 They found that batters do not follow the ball with their eyes all the way from a bowler’s hand to the bat. Rather they look at the ball as it is delivered, then move their eyes down to the point of bounce, and then up as the ballet travels to the bat (1343). In this sense batting is a predictive exercise. This means that once a prediction has been made if a ball moves laterally and changes its line there is a limit to how much a batter can adjust to that movement.

With all that in mind the maximum good length for a seam bowler is the place where the ball will travel to the batter after bouncing in less than 200ms. What determines that place will then depend on how fast the bowler bowls. To get the length we also have to add 1.22 metres given the batter generally stands around the popping crease to intercept the ball and delivery lengths are commonly measured from the stumps.

One other consideration is how the pitch may slow the ball after bouncing. So how much does a cricket ball typically slow down after bouncing? Here again there is experimental research that is helpful. Researchers in 2005 measured Turf wickets in England and found that the ball retains 84.8% to 92.5% at an average of 88.1% of its speed after bouncing.4 Other estimates include 88.7% with a range of 87.1%–90.2% by the same researchers in 20045, and 85.2%–90.4% by researchers in New Zealand in 1997.6 For our purposes here I will stick to the latest estimated average of 88.1%.

With that we can work out the maximum good length at a post-bounce ratio (PBR) of 0.881 with the following equation: $length = (((speed/3.6)*0.881)/5)+1.22$

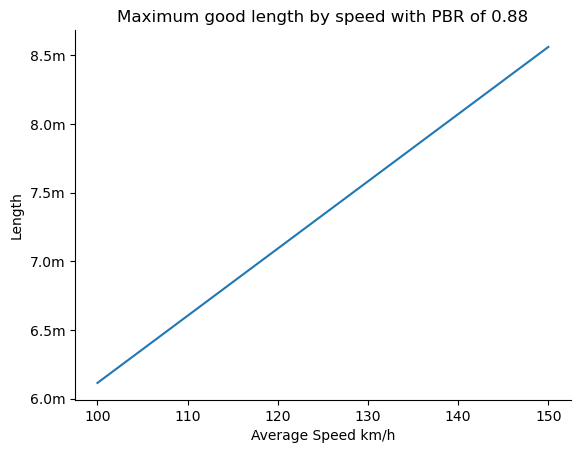

We can visualise this across a range of speeds in the following chart:

The interesting thing about this is that it shows that the difference between a max good length for a bowler averaging 130km/h and one averaging 140km/h is about half a metre. A larger difference than I would have guessed initially. Also it shows why faster bowlers have an advantage, they are able to bowl shorter (by design or through inaccuracy) since their deliveries can travel a greater distance in the 200ms than those bowling slower.

However, balls pitched at a good length that do not deviate enough (ie. less than half a bat’s width of 5.5cm) are of no use to a bowler. What this means is that at a given good length, there is also a minimum angle of deviation required. Using a little trigonometry we can see the equation to work that out is: $angle = \tan^{-1}(5.5/length)$

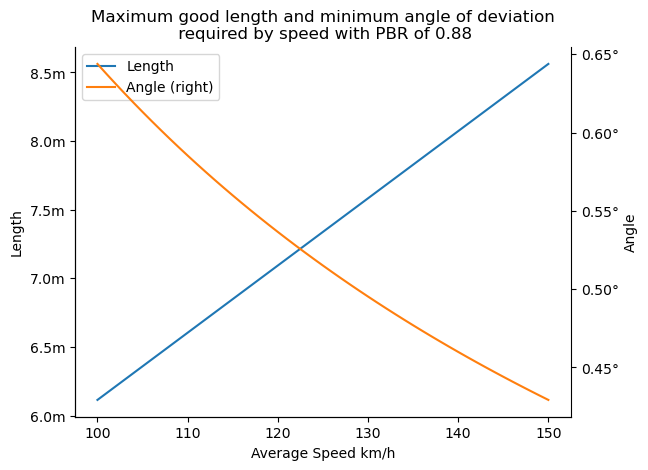

We can visualise this in the chart below:

The way to read the chart is to first take a given speed, go up to the blue line for the max length, then go up or down to the orange line at a particular speed and go right for the minimum angle of deviation required to miss or nick the bat.

What is interesting to me about this chart is how little deviation is required. Whilst there is no freely accessible data on angles of deviation, Cricviz has publicly reported at times deviations from seam bowlers upwards of 1 degree.7 But, the chart shows that at 130km/h bowling at around the maximum good length requires only half that amount of seam movement. It also shows how faster bowlers have an advantage as they can bowl shorter and as result require lower degrees of movement off the pitch.

What then is the minimum good length? A minimum good length is defined by the angle of deviation on offer since by definition if it is fuller than the maximum good length it will travel to the batter in less than 200ms. One issue in estimating this is that there is no freely accessible data on deviation off the pitch in cricket. Cricviz in social media has referred to instances of deviation of up to 2 degrees8, in articles to movement of 0.75 degrees as a large amount9, and reported on television of average movement in test matches between 1.1 degrees and 0.58 degrees.10 Using these figures as a rough guide and the following equation we can calculate the minimum good length: $length = (((5.5/\tan(angle))/100))+1.22$

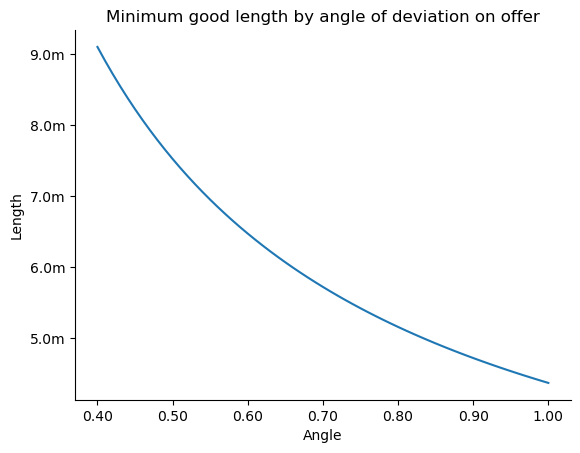

Looking at angles between 0.4 and 1 degrees, we can visualise the lengths below:

What is interesting for me is how the chart shows most degrees of seam movement are unplayable. For example, if some Test matches have offered average seam movement of up to 1 degree as reported on television, then that puts a window of good length for a seam bowler bowling at 140km/h between around 4.5m and 8m. That is a significant area on the pitch where batters face balls they cannot mechanically contact.

In this discussion, one thing I haven’t mentioned is how bounce affects length. It seems obvious pitching the ball up on bouncier wickets is advantageous as they are more likely to hit the stumps and so induce defensive shots that otherwise could be left alone. I’ve left out bounce as a consideration because it is hard to work out the vertical component of the ball’s velocity given it depends on the angle of delivery which in turn depends on the bowler’s release point. There is no good publicly available data on either of those things. Also there is a sense in which bounce probably plays a smaller role in the effect of getting wickets as bowlers need not threaten the stumps to get wickets.

I have also not mentioned swing as a form of movement or deviation. There are a couple of reasons for this. The first is that swing is a type of movement through the air largely before the ball bounces. As such, how much movement a bowler gets in this way is dependent on the length they decide to bowl, and whether they are delivering the ball in the right way. As such, there is no real way to claim a particular length is best for a bowler. Also, as we’ve seen from the research on how batters make contact with the ball, swing is largely about making the ball bounce in a different place to where the batter has predicted. Anything I have said above only applies to swing bowling insofar as there is deviation or continued swing after it bounces. If you want to learn more about swing bowling, I would recommend Aaron Brigg’s substack where he goes through the actual aerodynamics of swing and how best to describe it.

All in all, trying to work out the maximum and minimum good length has made me think that what batters and bowlers mostly need to do when first coming to the crease or when bowling is to estimate the post-bounce ratio. That is not to say they estimate it in a numerical sense, but more how much or less it is slowing compared to their idea of a neutral level so they can adjust their bowling or batting techniques. This might explain why many cricketers talk of pitches being skiddy, quickening up or being two paced.

What this all teaches us is that there really is no such thing as the good length for bowlers looking for seam movement. Rather, it is personal to each bowler within the conditions on offer. This is because a good length is a function of the limit of batter reaction times, a bowler’s speed, the post-bounce ratio for the pitch, and the angle of deviation on offer in the pitch.

-

See Nathan Leamon, “What is the best length to bowl in Tests?”, The Cricket Monthly, https://www.thecricketmonthly.com/story/1154076/what-is-the-best-length-to-bowl-in-tests ↩

-

McLeod, P. (1987). Visual Reaction Time and High-Speed Ball Games. Perception, 16(1), 49–59. doi:10.1068/p160049 ↩

-

Land, M. F., & McLeod, P. (2000). From eye movements to actions: how batsmen hit the ball. Nature Neuroscience, 3(12), 1340–1345. doi:10.1038/81887 ↩

-

James, D.M., Carré, M.J. & Haake, S.J. Predicting the playing character of cricket pitches. Sports Eng 8, 193–207 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02844162 ↩

-

James, D.M., Carré, M.J. & Haake, S.J. The playing performance of county cricket pitches. Sports Eng 7, 1–14 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02843969 ↩

-

McAuliffe KW, Gibbs RJ. An investigation of the pace and bounce of cricket pitches in New Zealand. Int Turfgrass Soc Res J 1997;8:109–119. ↩

-

See https://x.com/cricvizanalyst/status/1669686063932276739 ↩

-

See https://x.com/cricvizanalyst/status/1672918851397328908 ↩

-

See https://cricviz.com/mohammad-abbas-the-english-seam-bowler-they-never-had/ ↩

-

See https://www.reddit.com/r/Cricket/comments/nssdd7/seam_movement_on_day_1_and_2_since_2018_credit/ ↩