On Amour

Subscribe on Substack, via RSS/Atom, or follow me on Twitter for updates

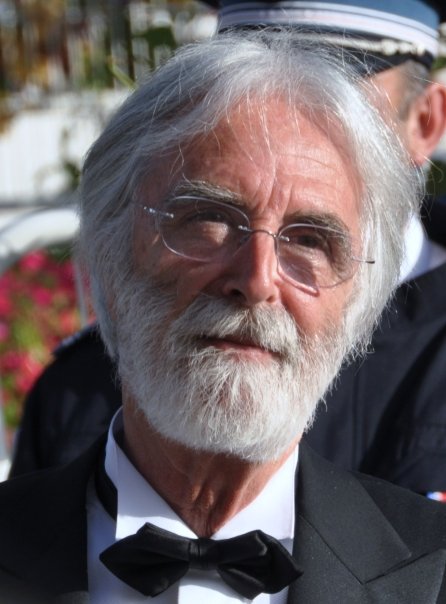

Michael Haneke’s, Amour, is unequivocally a masterpiece of modern cinema and most definitely one of the best films of 2012. The narrative is both clear and yet cinematically dense. Two things that are often difficult to produce on screen. The performances, particularly of the two leads, Emmanuelle Riva and Jean-Louis Trintignant, are realistic, subtle and seemingly effortless. Both performances communicate in volumes about the characters. The sound design is used not just for loud effects but to mark returning metaphors seamlessly. This post does does contain some spoilers about the climax in the film.

Haneke begins with Anne and Georges in their happy twilight years, enjoying their passion - music. The narrative begins its work from here, by marking Anne as a fiercely independent woman. It is into this retired bliss that Anne’s stroke leads to her being paralysed on one side of her body and dependent on Georges. The narrative from that point on is woven with sudden and crisp flashes of Georges imagination and memories of his once healthy vibrant wife. Almost every scene deals with the way relationships of love become almost too cruel to bear in the wake of inevitable death. A masterful scene is the seamless dream sequence in which Georges’s weariness, suffocation and sadness from caring for his wife are shown. The sequence works because Haneke has already marked early in the film the possibility of a robbery in the apartment. It is this latent fear that Haneke uses to heighten Georges’s nightmare as a metaphor for his current anguish. Another masterful scene is the one after which Georges kills his wife where he catches a pidgeon. The scene again works as cinematic moment because we expect Georges to kill the pidgeon since we have been shown his chasing a pidgeon out of the apartment earlier and we expect his violence to carry on. Presenting Georges simply petting the pidgeon cinematically develops the metaphor of his character as inherently non-violent and that he has euthanised his wife rather than murdered her.

Haneke begins with Anne and Georges in their happy twilight years, enjoying their passion - music. The narrative begins its work from here, by marking Anne as a fiercely independent woman. It is into this retired bliss that Anne’s stroke leads to her being paralysed on one side of her body and dependent on Georges. The narrative from that point on is woven with sudden and crisp flashes of Georges imagination and memories of his once healthy vibrant wife. Almost every scene deals with the way relationships of love become almost too cruel to bear in the wake of inevitable death. A masterful scene is the seamless dream sequence in which Georges’s weariness, suffocation and sadness from caring for his wife are shown. The sequence works because Haneke has already marked early in the film the possibility of a robbery in the apartment. It is this latent fear that Haneke uses to heighten Georges’s nightmare as a metaphor for his current anguish. Another masterful scene is the one after which Georges kills his wife where he catches a pidgeon. The scene again works as cinematic moment because we expect Georges to kill the pidgeon since we have been shown his chasing a pidgeon out of the apartment earlier and we expect his violence to carry on. Presenting Georges simply petting the pidgeon cinematically develops the metaphor of his character as inherently non-violent and that he has euthanised his wife rather than murdered her.

Emmanuelle Riva’s performance is outstanding in its detail and cinematic efficacy. Her slow degradation into complete paralysis and death is unnoticeable. Jean-Louis Trintignant, portrays the weariness and heartache of watching a loved one decay. He affects a limp suggesting that before his wife’s stroke he was the one expected to fall ill and that he is no way fit to be a full time carer. It is a testament to Haneke’s courage that he chooses not to explain but lets the performances communicate cinematically rather than as exposition.

The sound design is definitely a case of less is more - much much more. The absence of non-diagetic music throughout the film is in itself a cinematic metaphor. Apart from the fact that absence music gives us no respite from the narrative, it also works on showing Georges and Anne are not living with their passion. They are accomplished music teachers who have the harsh reality of death forced upon them.

It is reality that eventually consumes this film in the last scenes where Anne and Georges’s daughter Eva walks around the empty flat. It is the ugly reality of helplessness, lonliness and the absence for what we want most in a world that doesn’t stop.

Saranga Sudarshan

(photo by Georges Biard courtesy of creative commons)