Speculations on History

Subscribe on Substack, via RSS/Atom, or follow me on Twitter for updates

Sometimes we overestimate the past. Marian Maudsley at the end of L.P Hartely’s The Go-Between cannot see this. Still reliving the cross-class, social norm breaking relationship with the farmer Ted Burgess over 50 years ago, she boasts to the Leon Colston of the 1950s that people still come to visit and ask after what she did. But we know through her son that she does not in fact get many visitors and leads quite a lonely life. Her self-confidence has turned into delusion.

The past may be a foreign country, but it is more than that. It is a place that is superficially familiar enough that we draw specious links to it from our present. For instance, in India, the historical spectre of ‘the muslim rulers’ seems to haunt almost any discussion of the past. But if you visit some of the historical monuments that still survive of that period, as I did last winter, you realise how laughable it is. To come upon Tippu Sultan’s 18th century summer palace, one is surprised by its scale and meekness in comparison to the city that surrounds it. A squat two floor building of wood and plaster with several small rooms. A palace for a ruler in its day, but now set back from the busy market roads, it has no bearing on the India that surrounds it.

The disconnection with the past these monuments present does not necessarily have to do with their scale. Walking around the palace of Fathepur Sikri, it feels like you are stuck in a painting. Everything your eye meets is washed through with the deep flat red stones and elegantly manicured gardens. The hum of activity within the Jama Masjid courtyard isn’t from villagers going about their business or using it as a meeting place. It is the chatter of desperate voices trying to sell souvenirs, jewellery, handicrafts, to any passing tourist. Not much could be further from the power and splendour that thought to build the Buland Darwaza, a gigantic gate to the courtyard that dwarfs the voices seeking shelter inside it from the midday sun.

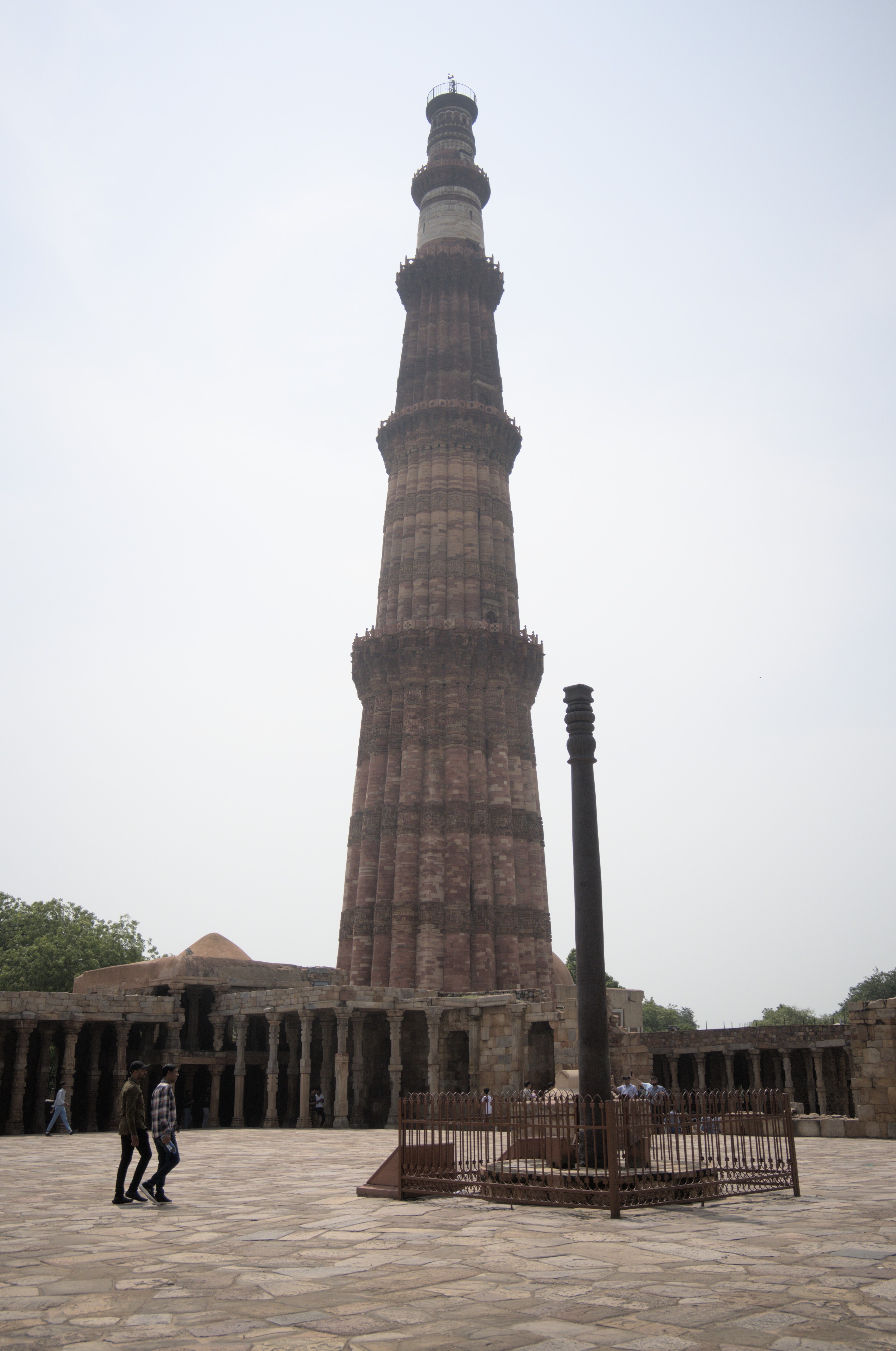

Another place that displays this strange disconnection is the Qutub Minar complex. A piece of triumphalist islamic architecture constructed 800 years ago to mark the Gurids conquering Delhi. What remains strange, at least to me, is that they saw fit to construct the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque in the centre of the complex with intact pillars from hindu temples, albeit with the idols removed. Why use such things at all? And, even stranger, they saw fit to place the Iron Pillar, a relic itself 800 years removed from the Gurids in the centre of the mosque’s courtyard. None of this fits a neat narrative of foreign invaders oppressing an ‘India’ that wasn’t even created yet. The only thing to feel or observe that makes sense in the present is the lost self-confidence of a previous age.

This feeling is not confined to India. Recently I read Vladislav Zubok’s Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union. It provides a sober non-moralistic history of the final years of the USSR. It’s an amazing account of an empire falling due to a revolution from within. The west did not defeat communism, and neither did they expect their victory. It is no surprise that when confronted with this both sides submerged themselves with invented pasts that offered convenient narratives about the present. The Americans, and the rest of NATO saw themselves as receiving the mandate of heaven in global affairs. Russia as the successor state to the USSR, saw itself as a betrayed European brother that must regain its position. These forces came to a head in Ukraine in 2022.

These narratives occur in different intensities. In India, it appears as Hindu nationalism and weird religious fervour. As I saw it last winter: rallying cries at ancient and supposedly solemn temples or unemployed saffron clad young men roaming the highways trying to return India to a mythical Hindu nation. This is accompanied by a general ignorance of Sarnath, only 8km from the centre of Varanasi, where one can actually come face to face with Indian antiquity. There one can bear witness to the immaculately preserved Lion capital of an Ashoka pillar from the 3rd century BC - the emblem of the modern Indian state.

In Australia, the narratives involve justifying the status quo on the basis that it is an incontrovertible improvement on the past or panicking that a long standing status quo is changing. Donald Horne in The Lucky Country describes Australian attitudes towards enjoyment as a rising paganism in the 1960s. This is a shift from the puritanism that dominated until the 1950s, in which drinking alcohol was generally frowned upon, laws closed at bars at 6pm, and liquor was generally not allowed at meals. The narrative in 2024 is that any change from the status quo of permissive alcohol use is an unthinkable limitation of civil liberties or a lamentable slide in the larrakin culture. What is more likely is that decreasing alcohol use may be a return to a long term trend and may actually be beneficial for public health.

A narrative that involves justifying the status quo is superannuation. Horne remarks that one of the worst things for an Australian in the 1960s was to grow old due to the inadequacy of the age and widows pensions. Rather than rectifying those welfare systems by universaling them and funding them by broadening the tax base in an egalitarian spirit, the left became obsessed with superannuation as the great solution to retirement. Even though superannuation merely involves workers forgoing wages and projects the lifetime inequalities of income into old age with a privatised retirement scheme riddled with convoluted tax arrangements.

There are of course numerous other examples of these status quo justifying narratives. The rise of personal car culture, the ripping up of the tramways in Sydney, the introduction of HECS, and the privatising of large state owned enterprises. But what lost self-confidence are these narratives a reaction to? Australia is neither an old country nor a recent super power. Perhaps it is that, as Horne describes it, a pragmatism or even malaise at the centre of Australian political life created an inordinately prosperous country in the twentieth century. This markedly non-idealistic spirit disappoints and so engenders a reinvention of the past as a country that solved the problem of social class, unlike the UK, and solved the problem of economic inequality, unlike the US. When, in reality it solved neither.